I have known black boys, known them in airless classrooms where the scent of their too-strong cologne worked overtime masking the cling of their sweat to skin and hormones. And I have known their scratching, grabbing, tugging at the belt loops of too-big pants, have involuntarily memorized the plaids and imprints on their boxers.

I have known boys like underripe fruit, a pit of eventual sweetness at the core of them, encased in a bitter pulp, toughening from too little tending or underexposure to light. I have watched them become principles in death when they were not finished learning what it would mean to be principled in life.

I have known them nursing dreams with slimming odds of realization, heard them reasoning with the wardens behind their private walls, scraping at the doors some white man’s stubborn shoulder intended to force closed.

Listen. You have heard them, smelled them, touched them, too. Groping boys. Maddening boys. Boys who, had they the luxury of longer lives, would grow to regret how they treated girls, how they dodged their daughters or fought the smallest dudes on the yard.

Had they lived, they would’ve shuffled home, hats in hand, hugged their mamas, clapped their daddies’ shoulders, nodded like men who understood remorse, who’d been leveled by regret and learned to talk about it.

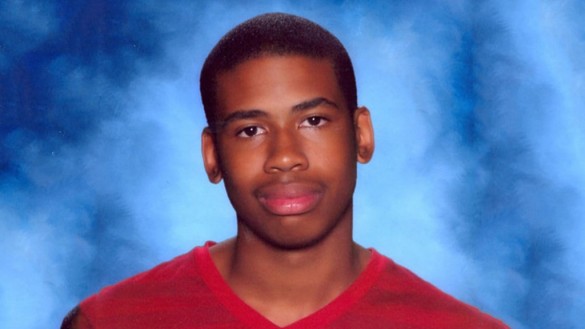

Had they lived, they would’ve borne enough concussions to concede their desire for millions at the the expense of unscathed minds. And maybe they would’ve been Marines like Jordan Davis hoped he might be, maybe aviators like Trayvon envisioned himself or husbands like Jonathan Ferrell and Sean Bell were so close to becoming. Maybe they would’ve grown to guess that the cost of longer life was a hunching of one’s height at a white woman’s door, a soft knock rather than the screams that often escape the frantic or crowded or injured. Maybe they would’ve conceived children with women with whom they couldn’t bear to live — and all over again, they would find themselves having to grow, to lean toward a quickly dimming light and to become tender when it was far more tempting to coarsen.

They would’ve learned to be less clumsy, less clawing, to kiss as though they had the promise of many unthreatened years. They might have lived long enough to make tenuous sense of the finite number of American fates black men meet, long enough to marry well, then poorly, then well again.

Perhaps.

But we are losing them too soon to know, while they are yet boys. We are replanting our underripe fruit, graveyards becoming our gardens, and tending far more memories of boys than moments with full-grown men. It gets harder to talk to these could-have-been-towering trees, these possibly-flowering plants whose fruits we’ll never know.

And every day, there are new boys among us. We raindance for them. Grow. Live. We campaign for them. Grow. Live. We keep them from harm even when harm might be their better mentor. Hide. Grow. Live. And we guess for them. Grow. Live. And we know for them. Grow! Live! Living alone never ensures what a boy will become, but black men, above all, are the boys spared long enough to live. This is the look of hope, our lowest bar to clear: boys reaching bullet-free adulthood and outreaching everyone’s fear.

Leave a comment