The first thing I am pocketing is your name. Tamir, like something uttered in prayer. We will all be saying it so much in the days to come, it will sound like a chorus of hushes in a holy place, a sacrifice, not of praise but of sorrow. I am drawing it close to me now, listening to the sound of it on my lips first, before all our commentary turns you into a cause, foreign and distant.

I’ve become adept at this, arriving at the scene early, committing key details to memory. After I turned your name — Tamir — over on my tongue, I Googled it. It means tall or owner of dates or palm tree or wealthy. Your father says you were, in fact, tall for your age. You were, in fact, wealthy in the ways that wind up mattering: of spirit, of intellect, of creativity. Twelve and already embodying the meaning of your name.

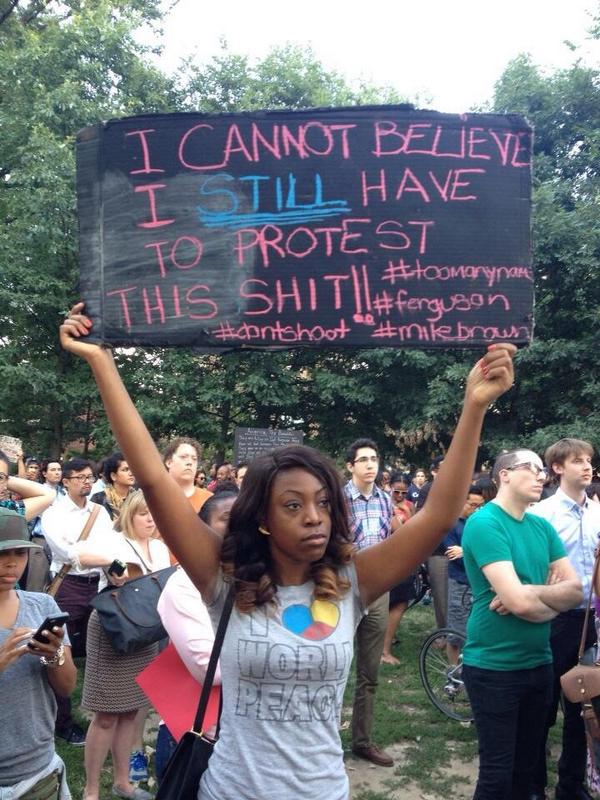

I will need to remember this, and it won’t be hard. I am sure you had heard of the boys and the girls before you, all gone before their time. I am sure that, by twelve, you may’ve had some sense that cops are not kind to black boys who are tall for their age. In death, you have joined an innumerable host of witnesses, carrying the truth of your final moments with you into eternity, while the rest of us spend years parsing speculation.

I’ve a system for marking tragedies like yours. I have taken to following your mothers on Twitter and checking your siblings’ Instagram accounts and listening to your fathers’ interviews, all for more insight into you. And I sigh with strangers and cry with strangers and try to conjure you as someone three-dimensional, someone whose breath I can imagine feeling on the back of my neck as you let out a raucous laugh with friends, while sitting behind me on a city bus.

You need to remain real for me, Tamir, because you were real and you were twelve and you had every right to reach adulthood, tangible and talking and marveling that you made it.

We all marvel at where we wind up when we’re grown. We think: Unbeknown, I could’ve gone to the mall with the shoplifting girls or rode in the backseat of an idling car whose driver had hopped out to rob someone.

I could’ve been pulled over by a cop while on a date with a guy who keeps an illegal gun and weed in his glove compartment.

I could’ve been asleep in my living room as SWAT raided the wrong black family’s house (or the right one’s). I could’ve been whiling away an afternoon in my yard or at a playground, like you were, when cops arrived, ready to shoot.

I could’ve made too little money to live in a safe community.

I could’ve lived in the “safest” community there is and still been black and still been murdered and still been blamed.

I could’ve made bad choices or had my good ones go unrewarded.

This could’ve gone so much worse.

Then we breathe deeply and honor the moment as it is: a better outcome, a sparing, a miracle.

We remember children and women and men like you most acutely in these moments, how maybe you were just minding your business, just daydreaming or playing pretend. Or maybe you were pleading to be seen as someone real.

Maybe your eyes begged: Before you unholster your weapon, look at the nubs of my fingernails. See how I chew them down till they bleed, how the pads of my fingers puff around them so that it’s hard to pop the tab on a soda can?

Before you disengage the safety, look at my left shin and the half-foot line of brown slashed across it. That’s where I wiped out on my bike when I was seven and tried not to cry because my boys were watching.

Before you rest your finger on the trigger, look at these waves in my hair. My uncle taught me how to brush along with the grain. Before you shoot, my daddy is around.

Before you shoot, I make my mama laugh. I am real. It makes me proud to make my mama laugh. I am human. I failed science. I am real. I stole a candy bar once. I am human. I might’ve planned to shoot this BB gun at birds. Before you shot.

We will never know what you were thinking, if you had time to think. We’ll never know exactly how afraid you must’ve been. You, specifically. Tamir E. Rice, twelve-year-old boy who died the day after being shot by police at a playground in Cleveland. You, whose eyes in the first photo released to the public, are soft and kind and so age-appropriately childish, the kind of eyes that couldn’t have known what else to do with a toy gun than play with it. We will never have the privilege of knowing you as anything other than teary anecdotes, than memories offered up to the court of public opinion as closing arguments.

But God help us if we ever stop imagining you, Tamir. Have mercy on our souls if we stop trying to resurrect you with vivid, near-futile envisioning. I am touching my hand to the tenor of your name in my pocket. Tamir. I am thinking of you as taller still, as wealthy in the way that should least matter. You are rich, and you are grown and, now, your eyes are more discerning. But there is still wonder in the glint of them as you marvel over where you’ve wound up. You think: I could’ve been mistaken for menacing. I could’ve pulled my airsoft pistol in a moment of play, and police may’ve been present, poised to kill me. Wouldn’t that have been wild? Wouldn’t that have been my family’s worst horror? You think, in your house made of crystalline air, your home in the Great By and By: Thank goodness I live in a world where things like that never happen.